AN ASSESSMENT OF THE MAJI-MAJI REVOLT IN TANGANYIKA (MODERN DAY-TANZANIA) 1905-1907

Usman Mohammad Musa, Ph.D

Department of History and War Studies, Nigerian Defence Academy, Kaduna.

&

Mahmud Dauda

Department of History and War Studies, Nigerian Defence Academy, Kaduna.

Abstract

This paper presents new insights on the Maji-Maji movement, which is a least studied research in the colonial history of Eastern Africa particularly Tanzania. Having use in-depth historical analysis of secondary sources as methodology, the paper examines the historical context of the Maji-Maji movement of 1905-1907which was a large scale war of resistance against German colonial rule in Tanganyika, (now Tanzania)that started in the Lindi Region and spread rapidly to other areas like the Ruvuma Region where the war ended. The paper opined that the immediate cause of the uprising was a government-instituted program of cotton culture, to which black farmers objected, but the underlying reason was a general resentment of harsh colonial policies that included forced labor and ruthless tax collection. The research also presentsthe movement as an armed movement arising from peasants’ grievances, backed by prophetic consecration as strategy to render the warriors’ immune to gunfire.The research reveals that the rebellion was however crushed through an effective strategy and tactics of scorch earth policy creating famine, huge loss of lives and properties and a lasting effect of untold hardship.

Keywords: Maji-Maji, Kinjkitle Ngwale, Akidas, Askaris, Tanganyika, Germany.

Introduction

After the Berlin Conference of 1884/1885 had provided a framework for a formal occupation of Africa, Germany consolidated its control over Tanganyika. Like every other colonial powers, the implementation of colonial policy, which often use to be forceful was part of the German’s colonial policy. The colony should be self-sufficient and as well aid her mother country with her agrarian prowess. The need for effective production of Cash Crops by the colonial society necessitated unfavorable working conditions, disproportionate wages and exorbitant taxation leading to aggression from locals. Obviously, breaking off the chains from the sturdy Germans would not come on a platter of gold, thus, Maji Maji movement – armed skirmishes intertwined with indigenous warfare beliefs as a strategy against the Germans was practically inevitable. It lasted for only two years but became one of the strategic historical revolts against oppressive colonial policy in the early 20th century. However, it is beneficial to note that the term Maji Maji is a Kiswahili term for “Sacred Water” which originated from Kinjekitile Ngwale who was the ritual leader of the movement. The water is a charmed medicine meant for the people to sprinkle, bath and rub into their bodies to protect them against German bullets.[1] This Maji became a symbolic and unifying factor throughout the war.

At the height of the rebellion came at Mahenge in August 1905 where several thousand Maji Maji warriors attacked but failed to overrun a German stronghold. On October 21, 1905, the Germans retaliated with an attack on the camp of the unsuspecting Ngoni people who had recently joined the rebellion. The Germans killed hundreds of men, women, and children. This attack marked the beginning of a brutal counteroffensive that left highly conflicting figures of Maji Maji warriors dead by 1907. The Germans also adopted famine as a weapon, purposely destroying the crops of suspected Maji Maji supporters.

However, it should be noted that the Tanganyika (now Tanzania) which came largely under the influence of Germany was through the efforts of the German Colonization Society, founded by Dr. Karl Peters. When Germany established its control over Tanganyika by 1898, it imposed a particularly violent regime in order to control the population, including a policy of killing kings who resisted German occupation.[2] This earned Peters, who was now the Tanganyika colonial governor, the name “Milkono wa Damu,” meaning “Man with Blood on His Hands.”[3] Throughout this period of German occupation, the African population was also subjected to high taxation and a system of forced labor, whereby they were required to grow cotton and build roads for their European occupiers.

Against this backdrop, this study was guided by the fact that a lot of works has been written on anti-colonial movements or rebellions in Africa with little or no distinct literature on the assessment of Maji Maji movements in German East Africa. So therefore, the thrust of the paper is to presents new insights on the Maji Maji movement that took place in Tanganyika (Tanzania) from 1905-1907 there by examining the factors that led to the movement, the nature of the revolts, the post rebellion conditions and the conclusion.

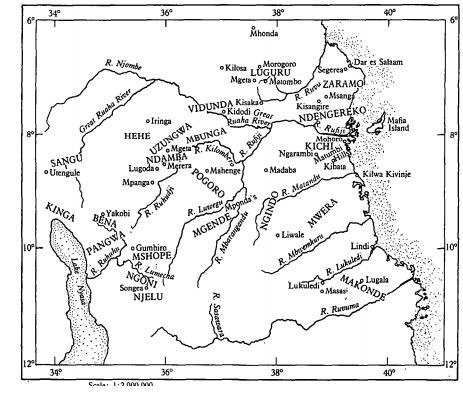

Source: Iliffe, John “The Organization of the Maji Maji Rebellion”, The Journal of African History, VIII, 3, (1967), 496. http://www.jstor.org/stable/179833

Remote and Immediate Causes of the Revolt

The Cotton programmer

One of the major causes of the Maji rebellion was cotton.[4] Largely by chance, the German government had first directed its programme to the highland settlement areas of the north but by 1900 the programme seemed to have failed and due to being desperate for revenue, the government turned to a policy of African cash crop agriculture, so they majorly concentrated on the south. In 1902, Governor Adolf Von Gotzen announced the adaptation of the programme that was borrowed from Togo which is situated in West Africa. Cotton cultivation was made compulsory but not by individual African farmers but on communal neighborhood fields, one at the headquarters of each recognized headman known as the Jumbe. The Akidas (who are the junior administrators of the Germans mainly Arab and Swahili people whose duty and responsibility is to collect tax) and the Jumbes were ordered to establish a cotton plot where Adolfs’ people would come to work. After the cotton had been sold, the plan was that the workers, the Akida and the Government would share the profits equally.[5] The programme actually failed as it was marred by the hardship to which those involved were subjected. Workers in the plantation were subjected to forced labor rather than a willing and voluntary force. Labor was controlled with brutal force and there was little motivation. The soil used for the plantation of cotton was unsuitable as the crops were poor. The marketing system also broke down and the subordinate officials pocketed the little cash they earned before it reached the producers. The Zaramo workers (they are the natives of Dar es Salaam district headed by Kabisila) refuse the 35 cents they were offered at the end of the first years work and this whole scheme created very strong incentives for a revolt.[6] So, the Maji Maji rebellion was against how the Germans interfered with how the farmers grew their crops and managed their land.

The advent of Arab Akidas

The compulsory and forced cultivation of an unprofitable cash crop was widespread grievance in southern Tanganyika but that was not the only major problem.[7] The Matumbi (are tribesmen who are natives to Kilwa District of the Lindi Region of Southern Tanzania headed by Lindimyo Machela hated the Arab Akidas and the Askaris who are Africans and Arab fighters that were recruited and appointed by the Germans to suppress resistance and exercise violence and oppression against the population.[8] The Matumbi had successfully rejected Arab influence by barring the Arabs from entering Matumbi; especially, they had refused to join the Arabs in slave trade and resisted them for many years. Under the German colonial administration, the Arabs were employed as Akidas and assigned especially to the coastal area to administer.[9] The Maji Maji rebellion was also against the Arabs who had now been given powers by the German colonial administration who for years had ruined their commercial and political efforts and they were also misusing their powers. Many people were captured and turned into slaves.[10]

Outrageous conduct of German officials

The Germans handled the Africans in Southern Tanganyika with extreme brutality.[11] On the slightest excuse, the Germans resorted to public flogging and to some extent they also killed their subjects. They also established a house tax (hut tax) on the Africans and they collected the tax with excessive force. The habit of German officials especially that of their mercenaries and house helps sleeping with their wives in circumstances which were a flagrant affront to Ngindo husbands and their punishment was by war against those who offended them and the Wangindo community were left with no alternative other than to fight the Germans.[12]

The Maji Maji Revolt

The oppressive regime bred discontent among the Africans, and resentment reached a fever pitch in 1905 when drought hit the region. A prophet—Kinjikitile Ngwale—emerged, who claimed to know the secret to a sacred liquid that could repel German bullets called “Maji Maji,” which means “sacred water.”[13] Thus, armed with arrows, spears, and doused with Maji Maji water, the first warriors of the rebellion began to move against the Germans, attacking at first only small German outposts, such as at Samanga, and destroying cotton crops. The rebellion spread throughout the colony, eventually involving 20 different ethnic groups all of whom wished to dispel the German colonizers. As such, it was the first significant example of interethnic cooperation in the battle against colonial control.[14]

In late July 1905, The Matumbi people decided to declare war on the Germans by destroying a symbol of their oppression under German rule, the cotton plant.[15] Armed with spears and arrows, on the 31st of July, 1905, Matumbi tribesmen marched on Samanga destroying the cotton crop and a trading post. In the aftermath of the attack, on August 4, Kinjikitle Ngwale who was the religious and ritual leader that was said to be possessed by a snake spirit named “Hongo” and provided inspiration for the anti-colonial struggle through the creation of Maji medicine (a mixture of castor oil and millets seeds) was hung for treason. However, prior to the death of Kinjikitle, he declared that the key to Tanganyika victory, the medicine that promised to turn German bullets into water, had spread as far as Kilosa and Mahenge.[16] After his death, on the 14th of August 1905, tribesmen attacked a small party of missionaries on a safari, spearing the missionaries to death. One of the men killed was Catholic Bishop Caspian Spiss. The next day, one hundred miles away, rebels captured a German post at Liwale. As Kinjikitle had promised before his death, news of and support for the rebellion spread across the territory. Rebels came together despite differences in culture and language to oppose German colonialism.[17] Throughout August the rebels attacked German garrisons throughout the colony, however they were unsuccessful in causing a large number of fatalities.

The common thread in many of the revolts, was the role of the maji; Kinjikitle’s medicine that promised to turn German bullets to water.[18] This medicine was put to the test on August 25th, when several thousand warriors marched on the German cantonment at Mahenge, which was defended by Lieutenant von Hassel. The two attacking tribes disagreed on when to attack, and this resulted in native casualties as the first attack was met with gunfire. Furthermore, the killing of individuals in possession of the Maji began to influence the masses that the Maji was not able to protect them, as it was promised to do.[19]

In October, the German government sent 1,000 soldiers to the territory to quell the rebellion. Bound for the Ngoni camp, the troops were to be utilized in the South to reinstate the German power structure. Heavily armed, the German soldiers purposefully eradicated the rebels’ food sources to weaken their men. While not an initial tactic, the famine following the Maji Maji Rebellion was orchestrated deliberately by German forces. Wangenheim reported on 22 October, “only hunger and want can bring about final submission. Military actions alone will remain more or less a drop in the ocean.”[20]Fighting finally subsided two years later in 1907, when German soldiers suppressed the last of the Maji Maji rebellion. While the death toll is a tangible expression of the loss suffered, the broken spirit of the natives was unquantifiable. Due to no fault of their own, the people of Tanganyika, fell victim to modern weaponry and the sheer numbers of the German forces combine with strategy and tactics of scorch earth that successfully inflict famine to break the resolve of the rebellious population.

Post-Rebellion Conditions

The areas affected by the Maji Maji Rebellion were utterly destroyed in the aftermath of the war. Southern Usagara was described as wholly unpopulated.[21] Uvidunda lost half of its total population.[22] A missionary estimated that over three-quarters of the Pwanga died in the war.[23]The total amount of African revolutionary deaths was ambiguous in the aftermath of the war. Anywhere from 75000 to 200000 Africans, or about one third of the area’s total population, perished throughout the course of the war.[24]

Furthermore, after the war, local power was primarily bestowed upon those loyal to the Germans during the rebellion. Kalimoto, prior the war an irrelevant sub-chief who, during the war, betrayed the Mbunga rebellion, became a leading chief of Umbunga and married the sister of Mlolere, the leading the most prominent Pogoro loyalist. The Hehe, loyal to the Germans, regained control of Usagara and parts of the Usangu and the Ulanga Valley. Most tragically, the survivors saw their old lands overtaken by forest and wildlife. Elephants entered Matumbi for the first time in living memory. These wild animals brought disease with them, contributing, along with famine, to many deaths. In Ungindo, the British came to create the largest game park in the world. Not only did the people of southern Tanganyika lose their battle to regain independence, but also they lost their long, millennia old battle with nature in the process.

This sad reality can be attributed to the fact that the German military’s institutional preference was to win the war with “total, unlimited force.”[25] The German military’s tendency to “gravitate towards final solutions,” rather than continue with lesser, more diplomatic operations was firmly ingrained in the psyche of the military’s hierarchy. This meant that rather than dealing with the rebellion in a peaceful and diplomatic way, the Germans preferred the destruction of their African territory. The harmful racist ideologies that the Germans, and other European colonizers, possessed were more of a result of imperialism than a cause of it. The heinous and brutal imperial practices that the Germans undertook to exploit resources from German East Africa developed the racist ideologies that justified the German Reich’s slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Africans, along with the post-war exploitation of the war survivors.This was the root of the German troops’ “spiral of revenge” that they practiced during imperial rule.[26]Three factors encouraged this spiral of revenge: the difficulty and frustrations of colonial warfare made worse by structural deficits in planning and administration, the enemy’s strange or “exotic” fighting practices, and the difficulties distinguishing civilians from warriors in guerilla wars.

Along with that, there were no outside factors at the time to stop German atrocities on the rebelling regions of German East Africa during and after the war. International law was widely thought of as inapplicable to a group of people that the western world believed were “expendable.”[27] Additionally, observers who did not hold these imperialistic, racist notions were largely absent, and, as a result, could not check the unrestrained violence the Germans committed on the Africans they subjugated prior to and in the aftermath of the Maji Maji Rebellion.

A famine swept across the Tanganyikan lands, proving the costliest in Ungoni and highland areas. This famine was spurred on through institutional racism spearheaded by unremorseful officers of the German Army. For instance, Captain Richter, who administered Songea in the aftermath of the rebellion, who “prevented cultivation and appropriated all food for his troops” was quoted saying: “The fellows can just starve.”[28]This, too, was the result of imperialistic notions of African inferiority.

Conclusion

In the light of the above discourse, the study has provided in-depth understanding, knowledge and clear picture of the causes and impacts of the nationalist movement/struggles from German East Africa Tanganyika (Tanzania) known as the Maji Maji movement of 1905-1907. The primary identity of the Maji Maji movement was as a result of the landmarks of oppression that arouse from the colonial plantations and policy’s imposed by the German authorities for communal cotton growing. The movement acquired an ideological content from prophetic religious leaders championed by a ritual leader who claimed to know and develop the secret war liquid medicine that could repel the German’s bullets. This ideology as argued by the paper enabled the rising spread of the movement and gave a degree of unity as well as became a symbol of unity and commitment to diverse peoples.The rebellion was however crushed finallyby the German’s in 1907 through an effective strategy and tactics of scorch earth policy creating famine, huge loss of lives and properties as well as a lasting effect of untold hardship.

The movements as argued in the paper no doubt brought negative repercussions like depopulation, destruction of people’s property, insecurity and other social unrest, it inspired future nationalism in Tanganyika. Although the Maji Maji Uprising was ultimately unsuccessful, but it forced Kaiser Wilhelm’s government in Berlin to institute reforms in their African colonies as they realized the potential cost of their brutality. Furthermore, the uprising and the mistakes in the poor methods of organization would become an inspiration for later 20th Century freedom fighters such as Mwalimu Julius Kambarage (who used these lessons to finally lead Tanganyika to political independence in 1961) and others who called for similar inter-ethnic unity as they struggled against European colonial rule.

Bibliography

Alexander, N. R., “ Evidence of the Maji Maji War in Matumbiland, Southeastern Tanzania”, (Unpublished B.A. Dissertation, University of Dar es Salaam, Dar esSalaam, 2008).

Beverton A., Maji Maji Uprising (1905-1907), accessed May 15, 2019, retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/maji-maji-uprising-1905-1907/, June 21,2009.

Gwassa G.C.K, and IliffeJ. The Records of the Maji Maji Rising: Part One. Nairobi: East African House, 1968.

Gwassa, G. C. K., “African Methods of Warfare During Maji Maji War 1905-1907”, Social Science Council of the University of East Africa, 1, (1969), 256-272.

Bachman K., and Kemp G., “Was Quashing the Maji-Maji Uprising Genocide? An Evaluation of Germany’s Conduct through the Lens of International Criminal Law”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol.35, Issue 2,July (2021), 235-249, https://doi.org/10.1093/hgs/dcab032.

Clement G. and Kamana G.,, The Outbreak and Development of the Maji Maji War 1905–1907, Cologne: RudigerKoppe, 2005.

Gregory A., “The Role of Women in Maji Maji War from 1905 to 1907 in Matumbiland, Ngindo and Ngoniland War Zones, Tanzania”, East African Journal of Education and Social Sciences EAJESS, Vol. 1, No. 3, October – December (2020), 52-59, https://doi.org/10.46606/eajess2020v01i03.0042.

Giblinn, J., Monson, J. Maji Maji: Lifting the Fog of War, Brill Press, 2010.

Iliffe, J. “The Organization of the Maji Maji Rebellion”, The Journal of African History 8 (3). Cambridge University Press, (1967), 495–512. http://www.jstor.org/stable/179833 or https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853700007982.

Iliffe J., A Modern History of Tanganyika, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Iliffe J., Tanganyika under German Rule: 1905-1912, Nairobi: East African Publication House, 1969.

Kamanga, K.C., “The Maji Maji War: An International Humanitarian Law Perspective”, Journal of Historical Association of Tanzania, 6(2), (2009), 47–65.

Molefi Kete Asante, The History ofAfrica: The Quest for Eternal Harmony, Florence, Kentucky: Routledge,2007.

Monson J., “Relocating Maji Maji: The Politics of Alliance and Authority in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania, 1870–1918,” Journal of African History, 39, no. 1 (1998): 95–120.

Mzee Mdundule Mangaya of Kipatimu, 1967, in Records of the Maji Maji Rising: Part One Nairobi: East African House, 1968.

Sadock, M.,“The Maji Maji War and the Prevalence of Diseases in South-eastern Tanzania 1905-1910”, (n.d.), http://research.com:8080/xmlui/handle/20.500.11810/2309.

Thomas P., The Scramble for Africa: The White Man’sConquest of the Dark Continent from1876 to 1912,New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

Robert G., and Kiernan B., The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Rushohora, N. A., “An Archaeological Identity of the Maji Maji: Towards an Historical Archaeology of Resistance to German Colonization in Southern Tanzania”, ResearchGate, August (2015), 1–263 pdf, https://doi:10.1007/s11759-015-9277-8.pdf

[1] N. A. Rushohora, “An Archaeological Identity of the Maji Maji: Towards an Historical Archaeology of Resistance to German Colonization in Southern Tanzania”, ResearchGate, August (2015), 3 pdf, https://doi:10.1007/s11759-015-9277-8.pdf.

[2] A. Beverton, “Maji Maji Uprising (1905-1907)”, retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/maji-maji-uprising-1905-1907/, June 21 ,2009, accessed March 15, 2022.

[3] J. Iliffe, Tanganyika under German Rule: 1905-1912, (Nairobi: East African Publication House, 1969), 37.

[4]Iliffe, Tanganyika under German Rule: 1905-1912, 38.

[5] C. K. Gwassa, and J. Iliffe, Records of the Maji Maji Rising: Part One, (Nairobi: East African House, 1968), 7.

[6]Gwassa, and J. Iliffe, Records of the Maji Maji Rising, 7.

[7] Mzee Mdundule Mangaya of Kipatimu, 1967, in Records of the Maji Maji Rising: Part One, (Nairobi: East African House, 1968), 15.

[8]K. Bachman and G. Kemp, “Was Quashing the Maji-Maji Uprising Genocide? An Evaluation of Germany’s Conduct through the Lens of International Criminal Law”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol.35, Issue 2,July (2021), 236, https://doi.org/10.1093/hgs/dcab032.

[9]Mzee Mdundule Mangaya of Kipatimu, 1967, in Records of the Maji Maji Rising, 19.

[10] J. Iliffe, “The Organization of the Maji Maji Rebellion”, The Journal of African History 8 (3).(Cambridge University Press, 1967), 495-496. http://www.jstor.org/stable/179833. (495-512).

[11] Iliffe, “The Organization of the Maji Maji Rebellion”, (1967), 510.

[12]Iliffe, 172.

[13]J. Giblin and J. Monson, Maji Maji: Lifting the Fog of War, (Brill Press, 2010), 6.

[14]Giblin and Monson, 8.

[15] Iliffe, 177.

[16]Iliffe, 178.

[17]J. Iliffe, A Modern History of Tanganyika, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 17.

[18] G. Robert, and B. Kiernan, The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 45.

[19]Gwassa, and Iliffe, Records of the Maji Maji Rising, 50.

[20]Iliffe, A Modern History of Tanganyika, 50.

[21] Iliffe, A Modern History, 50.

[22]Iliffe, A Modern, 50.

[23]Gwassa, and Iliffe, Records of the Maji Maji Rising, 50

[24]A.Beverton, “Maji Maji Uprising 1905-1907”, (21 June, 2009),Black Past, Global African History: BlackPast.org. accessed 29/04/2022, https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/maji-maji-uprising-1905-1907/

[25] Beverton, “Maji Maji Uprising 1905-1907”. 2009.

[26]Beverton, “Maji Maji Uprising 1905-1907”.

[27] Beverton, “Maji Maji Uprising 1905-1907”.

[28] Iliffe, A Modern History of Tanganyika, 51.